Once again, Cannes has been buzzing with one word: purpose. The theme this year is hypocrisy: the tainting of purpose by cynical brands quick to make a fast buck off the back of a feel-good campaign.

This has been brewing for a while. A few weeks back, Mark Ritson went as far as saying a true brand purpose doesn’t boost profit, it sacrifices it. He concludes that, “it’s crucial we draw a line between businesses that were founded from purpose and those that originated with a profit agenda and applied purpose to secure more of it.”

On many levels I agree. But it does oversimplify the argument because it implies that purpose is an absolute—that you’re either all-in or morally bankrupt.

Now, I know what I’m about to say will be unpopular. But it is OK to make money. Returning a profit to shareholders is the right thing to do. And big, established businesses can declare a purpose and have a positive societal impact while making profit.

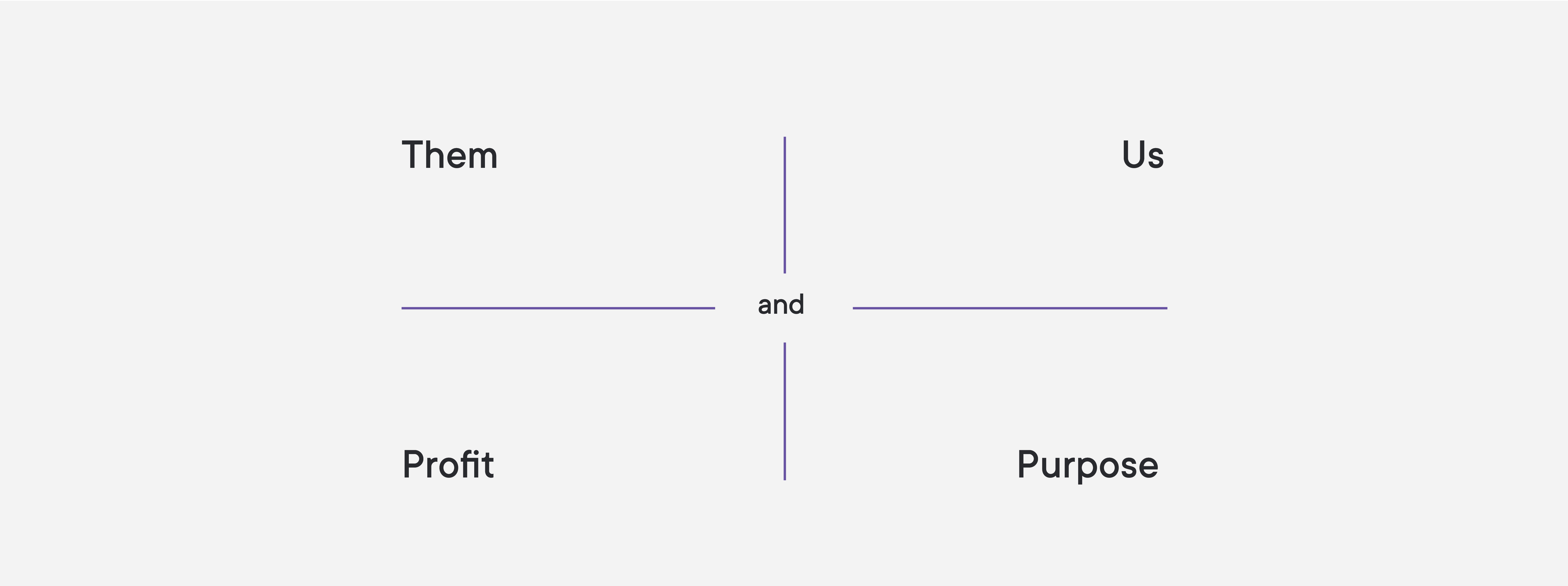

It’s easy – too easy – to say that the application of purpose to established brands is a cynical marketing ploy and while some time it is, making sweeping statements about purpose as a whole is defeatist. I don’t accept that there are purpose absolutes. It’s not black and white.

While the B Corps movement, which started in California, outlines a laudable framework of ethical standards, many companies will find it tough to change their legal structure to meet the stringent qualification requirements.* But that doesn’t make them evil. As Richard Branson puts it: “A business is simply an idea to make other people’s lives better.”